Monday, December 2, 2024

Even town fool has opinions on FOIA

Saturday, March 2, 2024

Observers comment on Assange extradition hearings

My thanks to Assange Defense Boston for organizing the Massachusetts State House rally on February 20 (above). Assange Defense Boston posted on X a couple of clips of me (below). Read more about "Me and Julian Assange" and see my images from the event.

Here (and embedded below) is a webinar from the European Association of Lawyers for Democracy and World Human Rights about the February 20 and 21 hearings in the UK High Court of Justice. And here (and embedded below) are discussions of journalists, diplomats, and others who were in the room for parts of the hearings.

"..it's not partisanship...this is about government accountability. You can not form coherent policy positions...unless you have the info on which to base them. That's what Julian Assange is about. That's what resisting his extradition is about"

— Assange Defense Boston (@AssangeBoston) February 23, 2024

Prof. Rick Peltz-Steele @UMassLaw pic.twitter.com/9ONm9RDxVz

"[Assange]developed this amazing idea abt freedom of information absolutism...When he founded WikiLeaks..to make the best use of this new democratizing instrument on the internet" Prof. Richard Peltz-Steele @UMassLaw, co-signee letter to @TheJusticeDepthttps://t.co/RJLoxdBue7

— Assange Defense Boston (@AssangeBoston) February 23, 2024

2/ pic.twitter.com/umiT9FAvQz

Tuesday, February 20, 2024

Assange Defense Boston rallies at State House

At the rally today, I spoke about my experience with freedom-of-information law and read parts of a letter from U.S. law professors to U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland. The letter asks the U.S. Department of Justice to drop Espionage Act charges against Assange and abandon the request for his extradition from the UK.

Freedom of the Press Foundation has more on the letter. My comments were based on, and the text of the letter can be found in, my February 16, 2024, post, "Me and Julian Assange."

The High Court in London heard arguments today that Assange should have a right to appeal to the courts over his extradition, which the British government has approved. Read more about today's proceeding from Jill Lawless at AP News. The case continues in the High Court tomorrow. Protestors crowded on the street outside the London courthouse today.

Photos and videos by RJ Peltz-Steele CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

|

| The sun shines at the Massachusetts State House. |

|

| The group sets up. |

|

| The crowd grows. |

|

| Committee organizer Susan McLucas introduces the cause. |

|

| Victor Wallace speaks. |

|

| A letter in support is read from U.S. Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.). |

|

| A speaker decries government secrecy. The s***-word might have been used. |

|

| A woman speaks to the intolerable cruelty of U.S. federal prisons. |

|

| Committee organizer Paula Iasella says that Assange is hardly alone in aggressive national security accountability, citing John Young's Cryptome. |

Friday, February 16, 2024

Me and Julian Assange

WikiLeaks founder battles extradition in UK courts

|

| Julian Assange, 2014 Cancillería del Ecuador via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0 |

I've said that about myself. I stole the notion and adapted the line from a personal hero, the renowned Professor Jane Kirtley, whom I was privileged to meet first in her legendary tenure at the helm of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press (RCFP). Professor Kirtley utters the line as a First Amendment absolutist, and she's right: I've met no one so thoroughly committed to a free press, and able to persuade you she's right to boot.

Access to information, or frustration over the lack thereof, when I was a university journalist was a major force that drove me to law school. I was a strident 23-year-old law student, a legal intern at the Student Press Law Center (SPLC) and a willing convert to the cause, when I first met Kirtley in person.

It was the 1990s. Bill had cheated on Hillary, and Milli Vanilli's Grammy was revoked. I was well convinced that the world would be a better place if there were no secrets at all: if governments kept open books, and everyone walked around with their hearts on their sleeves.

At the joint offices of the RCFP and SPLC, I had access to a closet that held all of the publications on freedom of information. I devoured them. I was ready to build my Utopia.

I'm as close to a freedom-of-information absolutist as you'll find.

I still say the line. But I admit, sometimes now I say it with less conviction.

Yesterday on NewsHour, a cognition expert said that we experience an increase in compassion and empathy as we age. That's it, I thought. That's why the utterly fictional characters on This Is Us made me cry like it was my own family. That's why I'm no longer so confident in my absolutisms. It's biology, and I can't help it. I'm getting old and soft.

In 2006, I was still strong. I knew right from wrong. I was an absolutist terror. That was the year that WikiLeaks was founded. That was the year that Julian Assange came into my life.

Julian Assange and I are the same age, born just months apart and a world away, in 1971. By the time I learned of him, we were 25, and his biography made me feel like I'd been sitting on my hands watching the world go by. He had hacked NASA when he was a teen in Melbourne. He was charged with computer crimes by age 20.

But he wasn't a ne'er-do-well; he obeyed a nascent code of ethics for a new, technological age. He is credited with originating "hacktivism." He showed what government, especially the U.S. military, was up to behind virtual closed doors. He was out to make the world better by pulling back the curtain. Unapologetic, radical transparency.

When Assange co-founded WikiLeaks in 2006, freedom-of-information absolutism was the ethos. Anyone in the world with access to secrets could pour them anonymously into Wikileaks's servers in Iceland: a deliberate jurisdictional choice for information laundering. The drop-box technology was sleek. The morality was a-, not im-. Wikileaks would publish it all. The democratic potential of the internet would be realized. All the citizens of the globe would judge. Brilliant.

There were remarkable successes. Notable was the "collateral murder" revelation, that U.S. soldiers had killed 18 civilians in a Baghdad helicopter attack in 2007. WikiLeaks also revealed the toll of friendly fire deaths, many of which had been covered up. Conclude what one would about the military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, the people whose lives were on the line, as well as families and voters back home, deserved to see the good, the bad, and the ugly of war.

And it wasn't just about war. WikiLeaks had big banks in the crosshairs (2011, 2013). In 2016, a trove of records (e.g., Toronto Sun) revealed that Hillary Clinton campaign head John Podesta had called Bernie Sanders a "doofus" over his criticism of the Paris climate accord. Good to know.

But after the Iraq War apex, things had started to unravel. WikiLeaks knew a lot; maybe too much. Its revelations tested the as close to ... as part of my mantra. Absolutism's gloss started to tarnish.

Is there really social good in forecasting troop movements, when soldiers would be slaughtered as a result? Even Julian Assange saw it: Unmasked middle eastern informants cooperating with western forces, and the informants' families, faced brutal retaliation by militias and dictators. It was hard to work the math on absolute transparency to make the benefits always outweigh the costs.

So in 2010, WikiLeaks forged an alliance with The Guardian, and later other news outlets. With absolutism baked into the technology, WikiLeaks had no way to sift information to ensure, quite literally, that people would not be killed as a direct result of publication.

Journalists do know how to do that; that ethical balance, to minimize harm, is the very essence of journalistic professionalism. So WikiLeaks would turn some of its information over to journalists, who would screen for the rare but real need for confidentiality.

The collaboration was rocky, short-lived, and at best only partly successful. The missions of absolute transparency and journalistic judgment were not so easily reconciled. The story has been told many times, for example in Vanity Fair's 2011 "The Man Who Spilled the Secrets," and still is dissected in journalism schools.

Fortunes changed for Julian Assange. Negative words such as "anarchist" and "seditionist" took the place of positive words such as "crusader" and "activist." Allegations of rape, which Assange denies vehemently, surfaced in Sweden, which sought Assange's extradition from the UK. Conspiracy theorists, who are not always wrong, alleged that the Sweden allegations were a ruse to bring about Assange's extradition to the United States, which had indicted him, from a jurisdiction that would accede more readily than England would.

In London, Assange sought refuge in the Ecuadorean embassy, where he lived for nearly seven years. Things got weirder. Why wouldn't they?, with Assange trapped in a physical building and a legal limbo. In rare public appearances, Assange looked rough: less his former satiny-minimalist fashion, slick mane, and lustrous confidence; more fist-shaking-old-man-in-a-robe, scraggly-beard, "get off my lawn" vibe.

Eventually the Ecuadoreans grew weary of the house guest who wouldn't leave. They called the cops, literally. In 2019, Assange was arrested. He has been in London's high-security Belmarsh Prison since. The United States has asked the UK to extradite Assange to face espionage charges, and the UK has seemed pleased to offload a lightning rod.

Is the U.S. extradition request about prosecution or persecution? As media struggle to make sense of Julian Assange—"Visionary or Villain?"—all indications are that if he lands in the United States, sending him to the stockade, if not the gallows, will be a bipartisan cause. The shift in American political attitude these intervening years toward a troubling receptivity to authoritarianism has flipped the script on WikiLeaks in the public imagination.

Some 35 law professors, including me, on Wednesday signed a letter to Attorney General Merrick Garland asking that the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) end its efforts to have Julian Assange extradited and that DOJ drop Espionage Act charges against him. I'll paste the text of the letter below.

The Freedom of the Press Foundation, which has coordinated efforts on the Assange matter, issued a press release about the letter. Below is the foundation's three-minute video take.

|

Echoing just that worry, U.S. Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) led off the forum. He has led lawmakers, he said, in asking the Garland DOJ to drop the charges and abandon the extradition. McGovern represents the Massachusetts Second Congressional District, which is a good chunk of the center of the commonwealth, west of Boston.

The Freedom of the Press Foundation forum revealed just how dangerous the situation has become for journalists in America, and how endangered might be some fundamental precepts of First Amendment law. One journalist commented in the forum that he has been sued by government for a prior restraint on the dissemination of lawfully obtained public records. This is basic Pentagon Papers stuff. But would the present Supreme Court uphold the sacrosanct no-prior-restraint doctrine?, forum participants asked.

Assange will have been in prison in London for five years this April. Beginning Tuesday next week, on February 20 and 21, the High Court of Justice in London will hear his case on a potentially dispositive procedural question. Previously, the British government approved extradition to the United States, and a lower court judge decided that that determination could not be appealed. So the subject of the hearing next week is to determine whether Assange may appeal the administrative disposition to the courts.

Boston Area Assange Defense

plans a rally in support of Assange on February 20 (flyer above) at the Massachusetts State House. The

group has been an active local organization advocating against

prosecution of Assange. I publicized the organization's rally and forum last year. A demonstration is planned similarly at the UK Consulate in New York City on February 20 (flyer at left).

LAW PROFS' LETTER TO U.S. AG RE ASSANGE, ESPIONAGE ACT

February 14, 2024

The Honorable Merrick B. Garland Attorney General

Dear Attorney General Merrick Garland,

The undersigned law professors strongly urge the Department of Justice to end its efforts to extradite WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange to the United States and to drop the charges against him under the Espionage Act.[FN1]

Our personal views on Assange and WikiLeaks vary, and we are not writing to defend them in the court of public opinion. But when it comes to courts of law, we are united in our concern about the constitutional implications of prosecuting Assange. As explained below, we believe the Espionage Act charges against him pose an existential threat to the First Amendment.

"[A] free press cannot be made to rely solely upon the sufferance of government to supply it with information."[FN2] Accordingly, the Supreme Court has correctly and repeatedly held that journalists are entitled to publish true and newsworthy information even if their sources obtained or released the information unlawfully.[FN3] Journalists have relied on sources who broke the law to report some of the most important stories in American history.[FN4] An application of the Espionage Act that would prohibit them from doing so would not only deprive the public of important news reporting but would run far afoul of the First Amendment.[FN5]

That is why last November, editors and publishers of The New York Times, The Guardian, and other international news outlets wrote in an open letter about the Assange case that "[o]btaining and disclosing sensitive information when necessary in the public interest is a core part of the daily work of journalists. If that work is criminalised,our public discourse and our democracies are made significantly weaker."[FN6] Additionally, top editors at The Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and more have unequivocally condemned the charges against Assange as a direct threat to their own journalists’ rights.[FN7]

The Obama/Biden DOJ recognized as much in declining to prosecute Assange, reportedly due to “the New York Times problem,” i.e., the lack of a legal basis to prosecute Assange that could not also be used to prosecute the nation’s most recognizable newspaper.[FN8] That was, unfortunately, less of a worry for the Trump DOJ, but should deeply concern your office.

The current indictment against Mr. Assange contains 17 counts of alleged Espionage Act violations, all based on obtaining, receiving, possessing and publishing national defense information.[FN9] The indictment accuses Assange of "recruit[ing] sources" and "soliciting" confidential documents merely by maintaining a website indicating that it accepts such materials.

Award-winning journalists everywhere also regularly "recruit" and speak with sources, use encrypted or anonymous communications channels, receive and accept confidential information, ask questions to sources about it, and publish it. That is not a crime—it’s investigative journalism. As long as they don’t participate in their source’s illegality, their conduct is entitled to the full protection of the First Amendment.[FN10]

The fallout from prosecuting Assange could extend beyond the Espionage Act and beyond national security journalism. It could enable prosecution of routine newsgathering under any number of ambiguous laws and untested legal theories.We’ve already seen prosecutors test the outer limits of some such theories in cases against journalists.[FN11]

The Justice Department under your watch has spoken about the importance of newsgathering and ensuring the First Amendment rights of reporters are protected, even when stories involve classified information. You have also strengthened the Justice Department's internal guidelines in cases involving reporters.[FN12] We applaud these efforts. But a prosecution of Assange under the Espionage Act would undermine all these policies and open the door to future Attorneys General bringing similar felony charges against journalists.

We respectfully urge you to uphold the First Amendment and drop all Espionage Act charges against Julian Assange.

Sincerely,

Jody David Armour, Roy P. Crocker Professor of Law, USC Gould School of Law

Michael Avery, Professor Emeritus, Suffolk Law School

Emily Berman, Royce R. Till Professor of Law, University of Houston Law Center

Mark S. Brodin, Professor, Boston College Law School

Leonard L. Cavise, Professor Emeritus, DePaul College of Law

Alan K. Chen, Thompson G. Marsh Law Alumni Professor, University of Denver Sturm College of Law

Carol L. Chomsky, Professor, University of Minnesota Law School

Marjorie Cohn, Professor of Law Emerita, Thomas Jefferson School of Law

Evelyn Douek, Assistant Professor of Law, Stanford Law School

Eric B. Easton, Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Baltimore School of Law

Richard Falk, Albert G. Milbank Professor of International Law and Practice Emeritus, Princeton University

Martha A. Field, Langdell Professor, Harvard Law School

Sally Frank, Professor of Law, Drake University School of Law

Eric M. Freedman, Siggi B. Wilzig Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Rights, Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University

James Goodale, Adjunct Professor of Law, Fordham University School of Law

Robert W. Gordon, Professor of Law, Emeritus, Stanford Law School

Mark A. Graber, Regents Professor, University of Maryland Carey School of Law

Jonathan Hafetz, Professor of Law, Seton Hall Law School

Heidi Kitrosser, William W. Gurley Professor of Law, Northwestern – Pritzker School of Law

Genevieve Lakier, Professor of Law and Herbert & Marjorie Fried Teaching Scholar, The University of Chicago Law School

Arthur S. Leonard, Robert F. Wagner Professor of Labor and Employment Law, Emeritus, New York Law School

Gregg Leslie, Professor of Practice; Executive Director, First Amendment Clinic, ASU Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law

Gregory P. Magarian, Thomas and Karole Green Professor of Law, Washington University School of Law

Carlin Meyer, Prof. Emerita, New York Law School

Anthony O’Rourke, Joseph W. Belluck & Laura L. Aswad Professor, University at Buffalo School of Law

Richard J. Peltz-Steele, Chancellor Professor, UMass Law School

Jonathan Peters, Chair of the Department of Journalism and Affiliate Professor of Law, University of Georgia

Aziz Rana, Incoming J. Donald Monan, S.J., University Professor of Law and Government,

Boston College

Leslie Rose, Professor of Law Emerita, Golden Gate University School of Law

Brad R. Roth, Professor of Political Science and Law, Wayne State University

Laura Rovner, Professor of Law & Director, Civil Rights Clinic, University of Denver

Sturm College of Law

Natsu Taylor Saito, Regents’ Professor Emerita, Georgia State University College of Law

G. Alex Sinha, Associate Professor of Law, Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University

Mateo Taussig-Rubbo, Professor; Director of J.S.D. Program, University at Buffalo School of Law

Hannibal Travis, Professor of Law, Florida International University College of Law

Sonja R. West, Brumby Distinguished Professor in First Amendment Law, University of Georgia School of Law

Bryan H. Wildenthal, Professor of Law Emeritus, Thomas Jefferson School of Law

Ellen Yaroshefsky, Howard Lichtenstein Professor of Legal Ethics, Maurice A. Deane School of

Law at Hofstra University

Signatories to this letter have signed in their individual capacities. Institutions are named for identification purposes only.

1. 18 U.S.C. §§ 792-798.

2. Smith v. Daily Mail Publ'g Co.,443 U.S. 97, 104 (1979).

3. See, e.g., Bartnicki v. Vopper, 532 U.S. 514 (2001); Florida Star v. B.J.F., 491 U.S. 524, 536 (1989); Landmark Commc'ns, Inc. v. Virginia, 435 U.S. 829, 830 n.1, 832 (1978); Okla. Publ'g Co. v. Okla. Cnty. Dist. Ct., 430 U.S. 308 (1977).

4. See, e.g., N.Y. Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 913 (1971) (per curiam).

5. Jean v. Mass. State Police, 492 F.3d 24, 31 (1st Cir. 2007) (Bartnicki barred liability for knowingly receiving illegal recording under criminal wiretapping statute).

6. Charlie Savage, Major News Outlets Urge U.S. to Drop Its Charges Against Assange, N.Y. Times, Nov. 28, 2022.

7. Camille Fassett, Press Freedom Organizations and News Outlets Strongly Condemn New Charges

Against Julian Assange, Freedom of the Press Foundation, May 24, 2019.

8. Hadas Gold, The DOJ's "New York Times" problem with Assange, Politico, Nov. 26, 2013.

9. 18 U.S.C. § 793; WikiLeaks Founder Charged in Superseding Indictment, Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of Justice, June 24, 2020.

10. Bartnicki, supra; Democratic Nat'l Comm. v. Russian Fed'n, 392 F. Supp. 3d 410, 436 (S.D.N.Y. 2019) ("Journalists are allowed to request documents that have been stolen and to publish those documents.").

11. Steven Lee Myers & Benjamin Mullin, Raid of Small Kansas Newspaper Raises Free Press Concerns, N.Y. Times, Aug. 13, 2023.

12. Charlie Savage, Garland Formally Bars Justice Dept. from Seizing Reporters' Records, N.Y. Times, Oct. 26, 2022.

Thursday, February 1, 2024

Naming rape suspects may draw criminal charges for journalists under Northern Ireland privacy law

|

| Bernard Goldbach via Flickr CC BY 2.0 |

The relevant provision of the country's Justice (Sexual Offences and Trafficking Victims) Act 2022. Attorney Fergal McGoldrick of Carson McDowell in Belfast detailed the law for The International Forum for Responsible Media Blog in October 2023, just after the law took effect.

The law applies to a range of sexual offenses including rape. The prohibition expires upon an arrest warrant, criminal charge, or indictment. If prosecution does not expire the prohibition on identification, it remains in force until 25 years after the death of the suspect. The act amended preexisting privacy law to afford comparable anonymity to victims.

I have deep experience with this issue, and it is fraught. Despite my strong preference for transparency in government, especially in policing, the law has merit.

I was a university newspaper editor back in ye olden days of paper and ink. My newspaper reported vigorously on accusations of sexual assault against a student at our university by a student at a nearby university. The accusations and ensuing criminal investigation gripped the campus.

We learned the identity of both suspect and accuser. We reported the former and concealed the latter. Discussing the matter as an editorial board, we were uncomfortable with this disparity. Having the suspect be a member of our own community and the accuser an outsider amplified our sensitivity to a seeming inequity. We did take measures to minimize use of the suspect's name in the reporting.

These were the journalistic norms of our time. Naming the accuser was unthinkable. This was the era of "the blue dot woman," later identified as Patricia Bowman (e.g., Seattle Times). The nation was enthralled by her allegation of rape against American royalty, William Kennedy Smith. In the 1991 televised trial, Bowman, a witness in court, was clumsily concealed by a floating blue dot, the anonymizing technology of the time.

Smith was acquitted. The case was a blockbuster not only for TV news, but for journalism, raising a goldmine of legal and ethical issues around criminal justice reporting and cameras in the courtroom.

There was no anonymity for Smith. I went to a Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) conference around this time, and the issues were discussed in a huge plenary session in a ballroom. The crowd exuded self-loathing for the trauma journalism itself had piled on Bowman. Objectivity be damned, many speakers beat the drums for the pillorying of the acquitted Smith.

The calculation in journalism ethics with regard to Smith, and thus to my editorial board, was that police accountability, knowing whom is being investigated, charged, or detained, and public security, alerting the public to a possible threat, or eliciting from the public exonerating evidence, all outweighed the risk of reputational harm that reporting might cause to the accused. Moreover, ethicists of the time reasoned, it would be paternalistic to assume that the public doesn't understand the difference between a person accused and a person convicted.

Then, in my campus case, the grand jury refused to indict. Our reporting uncovered evidence that the accusation might have been exaggerated or fabricated.

Our editorial hearts sank. Had we protected the wrong person?

My co-editor and I discussed the case countless times in the years that followed. We agonized. It pains me still today. Thirty years later, I find myself still retracing the problem, second-guessing my choices. It's like a choose-your-own-adventure where you feel like you're making the right choice each time you turn the pages, yet your steps lead you inevitably to doom.

Idealistically committed as we were at that age to freedom-of-information absolutism, we were inclined to the anti-paternalistic argument and reasoned that probably we should have named everyone from the start and let the public sort it out.

In our defense, a prior and more absolutist generation of norms in journalism ethics prevailed at the time. I was there at SPJ in the following years as leading scholars worked out a new set of norms, still around today, that accepts the reality of competing priorities and evinces more flexible guidance, such as, "minimize harm." Absolutism yielded to nuance. Meanwhile, the internet became a part of our lives, and both publication and privacy were revolutionized.

So in our present age, maybe the better rule is the Northern Ireland rule: anonymize both sides from the start.

I recognize that there is a difference in a free society between an ethical norm, by which persons decide not to publish, and a legal norm, which institutes a prior restraint. I do find the Northern Ireland rule troublesomely draconian. The law would run headlong into the First Amendment in the United States. Certainly, I am not prepared to lend my support to the imprisonment of journalists.

Yet the problem with the leave-it-to-ethics approach is that we no longer live in a world in which mass media equate to responsible journalism. From where we sit in the internet era, immersed in the streaming media of our echo chambers, the SPJ Code of Ethics looks ever more a relic hallowed by a moribund belief system.

In Europe, the sophisticated privacy-protective regime of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is more supportive than the U.S. First Amendment of the Northern Ireland approach. The UK continues to adhere to the GDPR regime since Brexit. The GDPR reflects the recognition in European law of privacy and data protection as human rights, to be held in balance with the freedoms of speech and press. Precisely this balance was at issue in 2022, in Bloomberg LP v. ZXC, in which the UK Supreme Court concluded that Bloomberg media were obligated to consider a suspect's privacy rights before publishing even an official record naming him in a criminal investigation.

McGoldrick wrote "that since Bloomberg most media organisations have, save in exceptional circumstances, elected not to identify suspects pre-charge, thus affording editors the discretion to identify a suspect, if such identification is in the public interest."

Maybe the world isn't the worse for it.

Wednesday, January 17, 2024

Police reform shines light on disciplinary records

|

| CC0 Pixabay via picryl |

There is room for disagreement over what police reform should look like. I'm of the opinion that it costs society more to have police managing economic and social problems, such as homelessness and mental health, than it would cost to tackle those problems directly with appropriately trained personnel. I wouldn't "defund" police per se, but I would allocate public resources in efficient proportion to the problems they're supposed to remedy. We might not need as much prison infrastructure if we spent smarter on education, job training, and recreation.

Regardless of where one comes down on such questions, there is no down-side to transparency around police discipline. Police unions have cried privacy, a legitimate interest, especially in the early stages of allegation and investigation. But when official disciplinary action results, privacy should yield to accountability.

Freedom-of-information (FOI) law is well experienced at balancing personnel-record access with personal-privacy exemption. Multistate FOI norms establish the flexible principle that a public official's power and authority presses down on the access side. Because police have state power to deprive persons of liberty and even life, privacy must yield to access more readily than it might for other public employees.

In September 2023, Stateline, citing the National Conference on State Legislatures, reported that "[b]etween May 2020 and April 2023, lawmakers in nearly every state and [D.C.] introduced almost 500 bills addressing police investigations and discipline, including providing access to disciplinary records." Sixty-five enacted bills then included transparency measures in California, Colorado, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, and New York.

The Massachusetts effort has come to fruition in online publication of a remarkable data set. Legislation in 2020 created the Massachusetts Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) Commission. On the POST Commission website, one can download a database of 4,570 law enforcement disciplinary dispositions going back 30 years. There is a form to request correction of errors. The database, at the time of this writing last updated December 22, 2023, can be downloaded in a table by officer last name or by law enforcement agency, or in a CSV file of raw data.

The data are compelling. There are plenty of minor matters that can be taken at face value. For example, one Springfield police officer was ordered to "Retraining" for "Improper firearm usage or storage." I don't see that as impugning the officer, rather as an appropriately modest corrective and a positive for Springfield police. Many dispositions similarly suggest a minor matter and proportional response, for example, "Written Warning or Letter of Counseling" for "conduct unbecoming"/"Neglect of Duty."

Then there are serious matters. The data indicate termination of a police officer after multiple incidents in 2021, including "DRINKING ON DUTY, PRESCRIPTION PILL ABUSE, AND MARIJUANA USE," as well as "POSING IN A HITLER SALUTE." Again, it's a credit to the police department involved that the officer is no longer employed there. Imagine if such disciplinary matters were secreted in the interest of personal privacy, and there were not a terminal disposition.

The future of the POST Commission is to be determined. It's being buffeted by forces in both directions. Apropos of my observation above, transparency is not a cure-all and does not remedy the problem of police being charged with responsibility for social issues beyond the purview of criminal justice.

Lisa Thurau of the Cambridge-based Strategies for Youth told GBH in May 2023 that clarity is still needed around the role and authority of police in interacting with students in schools. Correspondingly, she worried whether the POST Commission, whose membership includes a chaplain and a social worker, is adequately funded to fulfill its broad mandate, which includes police training on deescalation.

Pushing the other way, the POST Commission was sued in 2022, GBH reported, by police unions and associations that alleged, ironically, secret rule-making in violation of state open meetings law. Certainly I agree that the commission should model compliance in rule-making. But I suspect that the union strategy is simply obstruction: strain commission resources and impede accountability however possible. Curious that the political left supports both police unions and police protestors.

WNYC has online a superb 50-state survey of police-disciplinary-record access law, classifying the states as "confidential," "limited," or "public." Massachusetts is among 15 states in the "limited" category. My home state of Rhode Island and my bar jurisdictions of Maryland and D.C. are among the 24 jurisdictions in the "confidential" category.

"Sunshine State" Florida is among 12 states in the "public" category. In a lawsuit by the Tallahassee Police Benevolent Association, the Florida Supreme Court ruled unanimously in November 2023 that Marsy's Law, a privacy law enacted to protect crime victims, does not shield the identity of police officers in misconduct matters. (E.g., Tallahassee Democrat.)

Friday, September 15, 2023

£5.41m reg fine over energy traders' WhatsApps cautions attorneys also on retention, spoliation, FOI

|

| Electrical pylons on the Leeds-Liverpool Canal, England. Mr T via Geograph CC BY-SA 2.0 |

News of the fine has shaken up the British compliance sector. The case should grab the attention of compliance attorneys, of course, but also corporate counsel and government attorneys throughout the Anglo-American legal system.

Wholesale energy traders discussed market transactions on WhatsApp on their personal devices. Rules on market manipulation and insider trading require that communications "relevant" to trading be documented and retained for Ofgem review; the messages were not.

The enforcement action therefore represents a wake-up call, but not a new standard. The case probably resonated for two reasons. First, employee use of personal devices for communication is increasingly common, if not expected, and it's difficult to police. Second, WhatsApp is known for its end-to-end encryption, a feature that makes it appealing to users, but incompatible with regulatory transparency.

I'm not a fin reg wonk, but it was those characteristics of the case that caught my attention. The enforcement action should remind corporate counsel that record retention requirements cut across devices and applications and can even follow employees home. Moreover, when records might be perceived reasonably to have potential relevance in future litigation, the cost of non-retention in spoliation can be steep.

Similarly, the enforcement action should remind government authorities that neither non-public location nor software-driven encryption countermands record retention and freedom-of-information laws. Transparency law was once vexed by problems such as proprietary access and private location; it is no longer. Just ask Hillary Clinton about her State Department emails or Donald Trump about his bathtub war plans.

The enforcement action is Ofgem, Penalty Notice: Finding That Morgan Stanley & Co. International PLC Has Breached Regulation

8 of the Electricity and Gas (Market Integrity and Transparency)

(Enforcement etc.) Regulations 2013 (the REMIT Enforcement Regulations) (Aug. 23, 2023).

Monday, September 11, 2023

Ark. Gov swings again at state FOIA

Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders has proposed a bill to undercut the highly regarded transparency regime of that state's Freedom of Information Act.

I was at the Arkansas Capitol when a veritable mob of citizen opposition stopped an anti-transparency reform bill in the spring. Try, try again must be the Governor's m.o.

My friend and colleague Professor Robert Steinbuch testified effectively against the spring reform bill. Here he is telling Conduit News Arkansas why the newest incarnation is no good either.

UPDATE, Sept. 16. My understanding is that the bill was gutted this week. A substantially narrowed enacted version applies only to secret information about the governor's security detail. The matter was discussed on Arkansas Week.

Friday, May 19, 2023

NYPD seizes adorable dog, person too, in retaliation for video-recording in public, attorney-plaintiff alleges

A New York legal aid attorney was arrested, along with her dog, when she started video-recording police, and then she sued for civil rights violation.

|

| Harvey (Compl. ¶ 36) |

Griffard began video-recording with her phone. After she crossed the street at an officer's instruction, she started writing down NYPD car plate numbers. An officer refused to give her his business card upon her request, the complaint alleges. Instead, the officer handcuffed Griffard and arrested her, taking her and Harvey into police custody. She was held at the 79th precinct for eight hours, while Harvey, a nine-year-old Yorkie, was held in the kennel.

Admittedly, what caught my attention in the case was not so much the facts, head-shaking inducing as they are, but the story of Harvey. Journalist Frank G. Runyeon, reporting for Law360, and NBC News 4 New York, also were enchanted.

Griffard and her attorney, David B. Rankin, of Beldock Levine & Hoffman LLP, must have been conscious of Harvey's intoxicating adorableness, too, because they included gratuitous glamor shots in the complaint—as I've reproduced here.

|

| Harvey (Compl. ¶ 20) |

Griffard make no such claim, though, rather using Harvey as evidence to demonstrate her emotional distress at being separated from him and being given no information about his whereabouts while they were held—and, between the lines, to tug at the heartstrings and demonstrate the utter absurdity of her arrest and detainment.

One paragraph of the complaint does allege that seven-pound "Harvey was traumatized by the incident and now takes medication to treat his anxiety disorder." And the count of unreasonable seizure points out that "Harvey missed his dinner."

The case is Griffard v. City of New York, No. 512993/2023 (Sup. Ct. Kings County filed May 2, 2023).

Monday, February 27, 2023

Judge chides attorney for not wearing coat

Associate Justice Courtney Rae Hudson took to task attorney and Professor Robert Steinbuch, Arkansas Little Rock, my colleague and past co-author on freedom-of-information works (book, essay), first, for not wearing a coat over his button-down shirt in the Zoom argument on February 2, and then for not having asked advance permission to use a demonstrative exhibit. She had the court and counsel wait painfully while Steinbuch and his attorney-client fetched coats.

Steinbuch probably should've worn a coat. He told Justice Hudson he had not because it interfered with his handling of the exhibit, a statutory text, within the small space of the camera view. Good excuse, bad excuse; either way, Justice Hudson's handling of the matter was condescending and, coming as it did after Steinbuch's argument, felt more personal than professional. My impression as a viewer was that Hudson was the one who came off looking worse for the exchange.

Being an aggressive advocate for transparency and accountability in Arkansas, Steinbuch has many allies in mass media, and they were not as gentlemanly about what went down as Steinbuch was. The aptly named Snarky Media Report made a YouTube video highlighting the exchange. As Snarky told it, "Justice Hudson pulled out her Karen Card." Snarky also observed, with captured image in evidence, that "[s]everal times during the hearing Hudson appeared to be spitting into a cup."

More seriously, Snarky took the occasion to highlight past instances in which Hudson's ethics were called into question. Hudson (formerly Goodson), who was elected to the court in 2010, and her now ex-husband, a class action attorney, took two vacations abroad, valued together at $62,000, at the expense of Arkansas litigator W.H. Taylor (Legal Newsline). Hudson did report the gifts, and she said she would recuse from any case in which Taylor was involved.

Very well, but my suspicions of bias run a bit deeper. Hudson's vacation-mate ex, John Goodson, is chairman of the board of the University of Arkansas. (Correction, May 9, 2023: I'm told that Goodson ended his service on the board a year or so ago; I've not been able to ascertain the date.) One of Steinbuch's tireless transparency causes has been for Arkansas Freedom of Information Act access to the foundation funding of the university system in Arkansas, especially the flagship University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Indeed, Steinbuch wrote just last week (and on January 29), in his weekly column for The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, about that very issue in connection with secret spending at Arkansas State University. University System counsel have fought ferociously and successfully for decades to stop any lawsuit or legislative bill that would open foundation books to public scrutiny.

Goodson also has what the Democrat-Gazette characterized in 2019 as "deep political and legal connections around the state" with disgraced former state Senator Jeremy Hutchinson. Hutchinson is a nemesis of former Arkansas politician Dan Greenberg (a longtime friend of mine). After Greenberg lost the senate race to Hutchinson in 2010, Greenberg sued a local newspaper, alleging a deliberate campaign of misinformation. Steinbuch supported Greenberg in the suit. Though Greenberg was unable to demonstrate actual malice to the satisfaction of the courts, discovery in the suit revealed a problematically cozy relationship between the newspaper editor and Hutchinson.

The day after the oral argument in Steinbuch's case, Hutchinson was sentenced to 46 months in prison on federal charges of bribery and tax fraud—ironic, given that a false report of ethical misconduct was a rumor that Hutchinson had sewn about Greenberg in 2010.

I don't know; maybe Justice Hudson just gets really hung up on men's attire. She does hail from a conservative corner of Arkansas.

But a wise friend once told me, "Nothing in Arkansas happens for the reason you think it happens."

The case is Corbitt v. Pulaski County Jail, No. CV-22-204 (Ark. oral arg. Feb. 2, 2023).

Thursday, February 23, 2023

Grand juror in Ga. Trump probe says little

|

Pres. Trump leaves Marietta, Georgia, in January 2021. Trump White House Archives via Flickr (public domain) |

Grand juries in the American justice system are secret for reasons that even access-advocate journalists and scholars such as myself tend grudgingly to respect. So I was shocked to see this 30-year-old grand juror, "who has described herself as between customer service jobs" (CNN), appearing above a "foreperson" banner, on my TV this morning.

I'm not naming her here, because I think she has had her 15 minutes. Literally. And she ought not be lauded for her TV blitz, which says more about the desperate breathlessness of the 24/7 news cycle than it does about a millennial's cravings for Likes or secrecy in the criminal justice system.

The legal reality of the foreperson's bean-spilling is not really as dramatic as splashing headlines suggest. In common law and in many states also by statute, grand jurors are bound to secrecy. Georgia grand jurors take an oath to that effect. But experts have pointed out that the grand jury investigating Trump's efforts to "find" votes in Georgia is a special, ad hoc, grand jury, so not necessarily operating under the usual statutes, and that Georgia law authorizes grand juries, though not individuals, to recommend publication of their findings.

More importantly, the judge in the instant matter apparently told grand jurors that they could speak publicly, subject to certain limits. The foreperson here said that she's steering within those limits, which appear to disallow disclosure of information about specific charge recommendations and the deliberations among jurors.

For all the media hoopla, the foreperson actually said very little, only that multiple indictments were recommended and that Trump and associates are targets of the investigation. That much already was publicly known. She refused to say whether the jury recommended charges against the former President himself, only teasing, "You’re not going to be shocked. It’s not rocket science" (CNBC), and there's "not going to be some giant plot twist" (N.Y. Times).

The common law presumption of grand jury secrecy means to protect the identity and reputation of unindicted persons and the integrity of ongoing investigations. Both of those aims further public policy, especially in the age of the internet that never forgets. There is some argument at the margins about when grand jury secrecy should yield to legitimate public interest. Accordingly, grand jury secrecy at common law is not an absolute, but a presumption, subject to rebuttal.

The case for rebuttal is strong when a President of the United States is the target of investigation. If grand jury secrecy is not undone in the moment, it's sure to be leveraged loose in the interest of history. Secrecy in the grand jury probe of the Clinton-Lewinsky affair in 1998 was unsettled by Clinton's own public pronouncements about his testimony. The "Starr Report" ultimately left little to speculation.

In cases of lesser magnitude, journalists and judges, naturally, do not always agree on the secrecy-public interest balance, and modern history is littered with contempt cases that have tested First Amendment bounds.

In a textbook case that arose in my home state of Rhode Island, WJAR reporter Jim Taricani refused to reveal the source of a surveillance tape leaked to him from the grand jury investigation of corrupt Providence Mayor Buddy Cianci. In 2004, Taricani, who died in 2019, was convicted of criminal contempt and served six months' home confinement. He became a symbol in the fight for legal recognition of the reporter's privilege, and, in his later years, he lectured widely in journalism schools. A First Amendment lecture series at the University of Rhode Island bears his name.

Taricani worked closely with the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press (RCFP). A superb RCFP series on "Secret Justice" in 2004 included a now dated but still highly informative brief on grand jury secrecy, and the RCFP has online a multi-jurisdictional survey on grand jury access.

Brookings has a report on the Fulton County, Georgia, investigation, last updated (2d ed.) November 2022.

Wednesday, February 22, 2023

Assange defense group plans Boston/online panel

Accused of hypocrisy, the Biden Administration still seeks Assange's extradition from the UK to face charges of espionage in the United States. Assange presently is appealing approval by the British home secretary of the extradition request.

Having co-founded WikiLeaks in 2006, Assange long advocated for absolutism in the freedom of information. But when WikiLeaks received a trove of records from U.S. soldier Chelsea Manning, Assange did enlist the help of journalists to filter the material for public consumption in an effort to protect people, such as confidential informants whose lives would be at risk if they were named as collaborators with western forces.

Nevertheless, the subsequent publication of records in 2010 and 2011 outraged the West. The records included secret military logs and cables about U.S. involvement in Iraq and, as Al Jazeera described, "previously unreported details about civilian deaths, friendly-fire casualties, U.S. air raids, al-Qaeda’s role in [Afghanistan], and nations providing support to Afghan leaders and the Taliban." Especially damaging to western interests was a video of arguably reckless U.S. helicopter fire on Iraqis, killing two Reuters journalists.

Manning was court-martialed for the leaks. President Obama commuted her sentence in 2017.

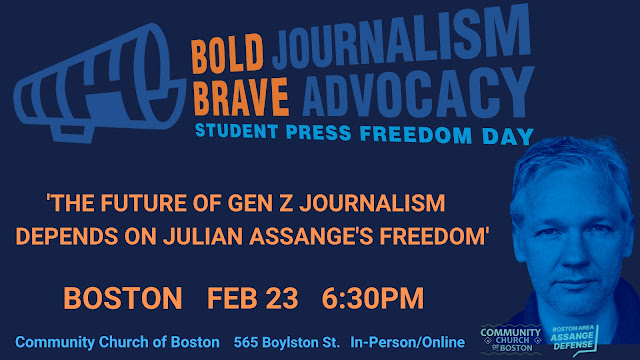

Thursday's program is titled, "The Future of Gen Z Journalism Depends on Julian Assange's Freedom." From Boston Area Assange Defense, here is the description.

Boston Area Assange Defense invites you to attend a panel discussion on how the U.S. prosecution of Julian Assange impacts the future of journalism. This event is part of the Student Press Freedom Day 2023 initiative: "Bold Journalism/Brave Advocacy."

The reality is that "Bold Journalism" has landed Julian Assange in a supermax prison for publishing the most important journalistic work of this century. Our First Amendment rights are threatened by this unconstitutional prosecution of a journalist and gives the US government global jurisdiction over journalists who publish that which embarrasses the US or exposes its crimes.

Prestigious international lawyer Prof. Nils Melzer (appointed in 2016 as UN Special Torture Rapporteur) authored, The Trial of Julian Assange, A Story of Persecution. The book is a firsthand account of having examined Assange at Belmarsh prison and having communicated with four "democratic" states about his diagnosis of Assange exhibiting signs of persecution. He wrote, "I write this book not as a lawyer for Julian Assange but as an advocate for humanity, truth, and the rule of law." "At stake is nothing less than the future of democracy. I do not intend to leave to our children a world where governments can disregard the rule of law with impunity, and where telling the truth has become a crime." Melzer stated, "If the main media organizations joined forces, I believe that this case would be over in ten days."

Boston Area Assange Defense platforms this experienced panel of journalists for a lively conversation about the Assange prosecution, its threat to journalism and the rule of law. Also, a short video clip narrated by Julian Assange's wife will be streamed for informational and discussion purposes.

Students and citizens alike are entitled to a free press so that we can make informed decisions.

A free press is the cornerstone of our democracy.

We must fight against censorship and the criminalization of journalism.

We must show "Brave Advocacy" to end the prosecution of Julian Assange!

Please join us February 23rd for this important "Bold Journalism/Brave Advocacy" event.

Students are invited so kindly share this event with your students!

Community Church of Boston's YouTube.

People will also gather at the Community Church of Boston, 565 Boylston St., near Copley Square.

An Assange information table will be set up with literature and petition to MA senators. Boston Area Assange Defense will be present to answer questions....

Guest speakers:

- Jeremy Kuzmarov, Author and Educator, Managing Editor, Covert Action Magazine

- Esther Iverem, Journalist, Producer, Radio Host, "On the Ground: Voices of Resistance from the Nation's Capital," nationally syndicated on the Pacifica Network

- Sam Carliner, Journalist; Sam's Jan. 2021 article covering the Dept of Justice DC rally during Assange's extradition hearing

- Tarang Saluja, Student, Activist, Journalist

Tuesday, January 31, 2023

Sunshine filters in to Mass. jail with gloomy history

Bristol County, Mass., Sheriff Paul Heroux is seeking to close a jail with a gloomy history, and last week he gave journalists a look inside.

Built in 1888, the Ash Street Jail in New Bedford, Mass., housed Lizzie Borden during the 1893 trial in which she was acquitted of killing her father and stepmother. The "Lizzie Borden House" is a tourist attraction in nearby Fall River, Mass., today. Undoubtedly the site of executions in Bristol County, Ash Street is often said to be the site of the last public hanging in Massachusetts, in 1898. Records conflict (compare O'Neil with O'Neill, and see Barnes), but if it's not, it's close enough. The commonwealth changed its method of execution to the electric chair in 1900.

|

| Purchase St., New Bedford, Mass., 1888. Whaling Museum photo via New Bedford Guide. |

Meanwhile, Hodgson was unapologetic for conditions within the jail. Former detainees complained of uncontrolled mold, uncontained sewage, and intolerable cold and heat (WBUR). The complaints have been controverted. A former jail official lauded staff and facility in a 2022 letter to the New Bedford Guide, for example, and a news reporter, upon a tour of the facility in 2016, wrote favorably of a modernized interior.

When Heroux toppled Hodgson in the 2022 election, closing the Ash Street Jail was part of his platform.

|

| President Trump and Sheriff Hodgson at the White House, 2019. Trump White House Archives via Flickr (public domain) |

In my 2012 casebook, Law of Access to Government, I contextualized Houchins with some biographical information about the sheriff (relying on sources such as the East Bay Times).

Thomas Lafayette Houchins, Jr., was a leader in the sheriff 's department in the 1960s and earned a reputation for uncompromising law enforcement. A veteran law enforcement officer, Houchins had joined the department in 1946 after serving in World War II as a Marine Corps fighter pilot. He was elected sheriff in 1975 and retired in 1979. In 1969, Houchins commanded a force of sixty or more deputies in crowd control at what became an infamously tragic concert headlined by the Rolling Stones. He recounted thirty years later: "Some guy jumped off an overpass because somebody told him he could fly. They lied. Another jumped into the [Delta Mendota Canal] because they told him he could swim. They lied to him, too.... I think we had five deaths and five births, so we came out even." Houchins died at his California home in 2005.

The Houchins case centered on news media investigation of the Santa Rita jail. Reporters wanted to tour "Little Greystone," a part of the jail in which "shocking and debasing conditions" were alleged to have caused inmate illnesses and deaths.

Houchins is one of a family of First Amendment access cases in which the Burger Court put the brakes on the liberal interpretations of the First Amendment that characterized the civil rights era. However, to the dismay of President Richard Nixon, who appointed him, Chief Justice Warren Burger was only marginally effective in rallying the Court to reverse the civil rights direction of the predecessor Earl Warren Court.

Houchins reflects that equivocation. Though Houchins's bar review flash card might read simply "no 1A access to public places," the decision came from a fractured Court of only seven justices and an opinion of only three. Harry Blackmun and Thurgood Marshall did not participate, the former having had recent surgery and the latter recusing. Burger was joined by only two others, including his successor as Chief Justice, William Rehnquist, in the opinion of the Court. They formed a majority of four with the addition of Justice Potter Stewart. (Read more about the fracas behind the scenes from Matthew Schafer.)

Concurring, Stewart joined Burger's conclusion on the facts of the case; he had been the author of two prior Court decisions, in 1974, rejecting press access to prisons or prisoners. Yet in his opinion in Houchins, he speculated that media might articulate a First Amendment claim on better facts. With three dissenters arguing at least as much, thus outnumbering the Burger contingent, Houchins arguably left the jailhouse gate open to a First Amendment theory, if you'll forgive the metaphor. Media law aficionados will recognize a pattern akin to Branzburg v. Hayes (1972), in which similar equivocation on the Court, aided later by clever advocacy from media lawyers, left the problem of constitutional reporter's privilege in disarray.

Much of the dispute in Houchins can be characterized as a frame-of-reference problem. In its broadest frame, Houchins is about public access to places to hold public officials accountable. That seems reasonable. But when I teach Houchins, students are quick to find the media position untenable, reading the case more narrowly as about reporters demanding access to any part of the prison, perhaps even with minimal advance notice.

That dichotomy in framing plays out in the public protests and media frustration over access to the Ash Street Jail in recent decades. There were tours; the writer who toured Ash Street in 2016, cited above, was then a reporter for public radio WBUR. Just like in Houchins, protestors and former detainees of the facility complained that public tours were limited and staged, showing reporters only what officials wanted them to see. Officials said that wider public access would jeopardize the security of the facility and the people inside, both detainees and workers.

The theoretical solution that emerged from Houchins, such as the case held, is that supervision of "non-public public places" should be accomplished not through the free press of the First Amendment, but through political accountability at the ballot box. To some degree, that's what happened when Heroux became sheriff in 2022. At the same time, prison conditions raise a peculiar problem in majoritarianism, familiar in criminal justice and civil rights contexts, and resonant in debate today over policing: The political system is not a reliable way to protect the rights of jailed persons, a minority class widely regarded with little sympathy.

On balance, I don't know whether the truth of the Ash Street Jail is closer to the horrifying complaints of former detainees or to the confident assurances of public officials. Whether constitutionally or statutorily, sunshine must be allowed to penetrate prison walls.