Open educational resources (OER) are all the rage in higher education, but the cost of hard copies for students remains a problem.

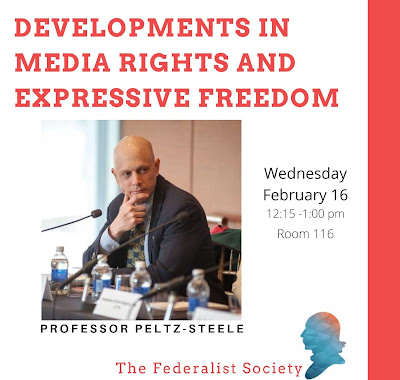

At a panel on OER at a UMass Dartmouth teaching and learning conference in January, I had the privilege of talking about my experience using Tortz, my own textbook for 1L Torts (chapters 1-7 online, remainder in development and coming soon). Ace librarian Emma Wood kindly invited me to co-pontificate with Professor Elisabeth Buck and Dean Shannon Jenkins on a panel, "The Price is Wrong: Lowering Textbook Costs with OER and Other Innovations." Wood is co-author, with law librarian Misty Peltz-Steele (my wife), of Open Your Casebooks Please: Identifying Alternatives to Langdell's Legacy (on this blog).

My campus is pushing for OER, and for good reason. We all know how exorbitant book costs have become for students. And academic authors are hardly beneficiaries of the proceeds. The first book I joined as a co-author in 2006, for 1L Torts, bore a sale price in the neighborhood of $100. I received $1 to $2 per book (and gave to charity the dollars generated by my own students). My students for the last two years have paid nothing for Tortz. Besides the cost savings, I get to teach from materials I wrote, compiled, and edited, so I know the content and how to use it better than I could anyone else's.

My students' book for 1L Property this past academic year cost $313. It's an excellent book, and I'm not knocking the professor who chose it. Developing my own materials for a foundational course is a labor-intensive project that I felt I could tackle only with the freedom, afforded by tenure, to set my own agenda, and some 20 years' experience teaching torts. At that, I've benefited and borrowed heavily from the pedagogy of a treasured mentor, Professor Marshall Shapo. Without the opportunity to have invested in Tortz, I'd be using a pricey commercial book, too.

A necessary aside: Technically speaking, my book is not OER, because I retain copyright. By definition, I'm told by higher education officials, "OER" must be made available upon a Creative Commons license, or released into the public domain. That's an irrevocable commitment. I'm not willing to do that. In my experience working with higher education institutions around the world, I have found that some out there would seize on freely available intellectual property while profiting handsomely from students desperate for opportunity. In such a case, I would rather negotiate a license and decide myself what to do with any proceeds. I freely licensed Tortz to my own students for the last two years. This is an interesting problem, but for another time.

So Tortz has been working out well. But now I'm looking at a roadblock: hard copies.

For the past two years, I have taught Torts I and II only to small night classes, and I've provided them with hard copies of the text. I made the hard copies on our faculty copiers, and the numbers were small enough not to be of concern for our budget. But beginning in the fall, I'll have two sections of torts, day and night, anticipating 70 or so students. That's too many prints to fold hard copies into the office budget.

I need my students to have hard copies for many reasons. The first issue is comprehension. For me, a reader of a certain age, I still have trouble absorbing content from a screen as well as from a page. When it's important for me to get it, I print a hard copy to read. Many of my law students, of all ages, but especially non-traditional and part-time students, share my preference. When I did a peer teaching observation for my colleague in property law, I saw students using both online and hard-copy versions of the $313 book. A hard-copy user told me that she uses the online version, but still needs to highlight and "engage with the text" to process the content on the first go.

A second issue arises in the exam. I prefer to give my 1L students an open-materials but closed-universe exam. I find that a closed-book exam tests more memorization than analytical skill, while an open-universe exam tests principally resistance to distraction. Regardless, it's my pedagogical choice. The problem is that the exam software we use locks students out of all computer access besides the exam. For any materials they're allowed to have, namely, the book, they need to have an old-fashioned hard copy.

So how to put hard copies in 70 students' hands without re-introducing the cost problem?

As is typical, my university has a contract with a bookstore operator, and book sales are supposed to go through the bookstore. The bookstore uses a contractor for printing. The contractor, XanEdu, after weeks of calculation, priced my book for the fall semester only: a ready-made PDF of 619 pages with basic RGB screen (not photo-quality) color, at $238 per print. That's a non-starter.

Printing at Office Depot would cost just a bit more than that. My university no longer has a print center, but I think its prices when there was one were comparable to retail.

A print-on-demand company, Lulu, was founded by Red Hat tech entrepreneur Bob Young, who became frustrated with the traditional publishing industry when he wanted to tell his own story. Lulu priced out at just $27 per book, which definitely makes one wonder what's going on at XanEdu. Lulu charges about $12 to ship, USPS Priority, but that takes up to 11 business days, which is far too long for students to order only once school starts. Also, it's not clear to me whether I can offer print on demand consistently with the university's bookstore contract. The bookstore has not answered my query as to what the mark-up would be to pre-order copies in bulk from Lulu.

I've kicked the issue upstairs, so to speak, to the law school administration. The associate dean promised to take the question up more stairs, to the university. Budgeting is above my pay grade, after all. I'd like to see the university support OER by volunteering to eat the printing costs. If I'm pleasantly surprised, I'll let you know. It's more likely the university will offer to deduct the costs from my pay.

Anyway, I am excited about OER, or freely licensed "OER," as a game changer for me to be more effective in the classroom. I appreciate that my university supports the OER initiative at least in spirit, and I am grateful to have been included in Emma Wood's thought-provoking discussion with Professor Buck and Dean Jenkins.